The following are entries from my blog posted in early January of 2011. As usual, I've left out the irrelevant matters as much as possible, but have kept the content entries as they were, except for when I wanted to add or subtract something, including places where it was obvious that something needed correction or clarification. I ran across one fragmented sentence, for which I couldn't figure out what I had meant to say at all. Hopefully it just got amputated in the process of copying the material. (I'm afraid to go back to see what actually made it onto the first public version.) In short, it's the same, except where I've changed it.

vv 1&2: After Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of King Herod, wise men from the east arrived unexpectedly in Jerusalem, saying, “Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we saw His star in the east and have come to worship Him.”(HCSB)

So, who were these "wise men" anyway? I'm intrigued by the fact that "wise men" has become the phrase of choice, at least among Protestants (or in German, die drei Weisen aus dem Morgenland), because it is so amazingly bland. (According to Roman Catholic lore, they were three kings, named Caspar, Melchior, and Balthazzar. The one whose picture is seen on the top right of this page is only rarely associated with them. His name is Fred, and just as with the other magi, not much is known about him.)  Lew Wallace, author of the book Ben Hur (1880), which preceded the movie, goes to great lengths to portray them as three philosophers from three different ancient cultures, but, again, as entertaining as his characterization is, it has no foundation in the known facts of history. "Wise men" would not necessarily be the best translation for the Greek magoi, as it appears here in Matthew, or the Latin magi, by which we are used to refer to these men in the biblical context. There are a number of thoughts about them that come to my mind.

Lew Wallace, author of the book Ben Hur (1880), which preceded the movie, goes to great lengths to portray them as three philosophers from three different ancient cultures, but, again, as entertaining as his characterization is, it has no foundation in the known facts of history. "Wise men" would not necessarily be the best translation for the Greek magoi, as it appears here in Matthew, or the Latin magi, by which we are used to refer to these men in the biblical context. There are a number of thoughts about them that come to my mind.

As always, when I begin to try to share technical historical matters with you, I put more on my plate than it is reasonable for me to write or to expect you to read in one sitting (not that I actually write things from off a plate). So, I will leave off here and pick up with the bizarre world of the magi next time. As you will see, the magi are a conspiracy theorist's dream.

v. 12: And being warned in a dream not to go back to Herod, they returned to their own country by another route. (HCSB)

v. 12: And being warned in a dream not to go back to Herod, they returned to their own country by another route. (HCSB) We were discussing the phenomenon of the magi who stopped at King Herod's to get directions to the new-born king of the Jews, which was, of course, the baby Jesus, about whom Herod had no notion. Given the ambivalence of the information I brought up last time, let's settle on the idea that by the time that Matthew mentioned the magi, the word had several ranges of meaning. In its most generic sense it could refer to someone who was an expert on the supernatural, a "wise man" in its most literal sense. Then it could also refer to someone versed in magic (and that word is, of course, related to the term "magi"

But then there is also the highly specific meaning, namely a Persian, or, if we go back far enough, a Medan priest. Apparently, the magi were around already prior to Zoroaster, adapted their rituals to the highly syncretized Zoroastrianism which was popular during the time of the Achemenid kings, and maintained it underground until Zoroastrianism became the state religion of Persia in AD 226 under the Sassanid dynasty. Let me make a quick chart of these different eras.

| Time Period | Form of Religion |

| Pre-Zoroaster | Polytheism; worship of the daevas, similar to Vedic religion in India |

| Zoroaster, who was contemporary with Cyrus, but geographically separated | Monotheism. Moral Dualism of God (Ahura Mazda) with his seven Amesha Spentas vs. the evil spirit Angra Mainyu and the daevas. |

| Achaemenid period, the time of the great kings: Darius, Xerxes, Artaxerxes, ets. | Zorastrianism adopted by the kings and the people, but also included deities and practices from the pre-Zoroastrian times. Previous gods were considered to be high angels. |

| Seleucid and Parthian periods | Zoroastrianism disappears, religion centers on Mithra, a god of light. |

| Sassanid period | Zoroastrianism reappears, much closer to Zoroaster's teaching than previously. Ritual dualism. |

| 7th century; Islamic invasion | Zoroastrianism remains as a small persecuted minority in Persia; its majority emigrates to India, particularly in the area of Bombay. |

So, Zoroastrianism went off the landscape for a time, but when the Sassanid dynasty finally reestablished a Persian kingdom in the third century AD, they made Zoroastrianism the state religion. (This is also the time in which many Jews moved to Persia ("Babylon") after the defeats by the Romans and completed the Talmud, among other things.) So where was this Zoroastrianism hidden all of this time? Apparently it was the magi who kept track of the religion and its rituals even though they themselves did not practice it externally. They became the custodians of a moribund religion and obsolete texts, and it's a complete mystery why they did so. Later data show that at the time that Zoroastrianism was re-established in Persia, they were the guardians of its orthodoxy, and, subsequently, they also added numerous writings to the Avesta, the collection that serves as Holy Book in Zoroastrianism, a small part of which probably goes back to Zoroaster himself.

As a fascinating example of their care for detail, they maintained a precise figure for the time of Zoroaster's flourishing, and there is no plausible explanation of why they might have contrived (viz. invented) this figure, namely 258 years before Alexander the Great. Some people have tried to find a rationalization why the magi might have created this number as a pious fiction. One rationalization goes like this. Later Zoroastrianism believed that time was divided into three eras, each of which was subdivided into three sub-eras of a thousand years in length. At the end of each thousand-year period after Zoroaster, a messianic savior-figure would appear, the first one bearing the name of Aushetar. So, sometime early during the Sassanid period, the magi concocted a chronology by which the coming of the coming of Aushetar would be imminent. Thus, if you adjust the data appropriately, you can work out the needed time span roughly in this fashion:

| Era | Time Span | Accumulated Time |

| Life of Zoroaster | 628-551 BC | 77 years |

| Achemenid period | 558-330 BC | 228 years Cumulative total: ca 300 years |

| Time of Alexander | Destruction of Persepolis in 330 BC. |

|

| Seleucid and Parthian kingdoms | Roughly 300 BC to 200 BC. | 500 years Cumulative total: ca 800 years |

| A short time into the Sassanid period when the magi set down their chronologies. | Let's say ca. AD 400 | ca. 200 years plus the 800 years above = 1,000 years |

Well, look at that! It's time to get ready for the coming of Aushetar! I know that this table fudges a little bit (or, more accurately bends matters with a heavy hand), particularly by picking the date of ca. AD 400 totally arbitrarily for the time of the construction of this chronology. However, I hasten to add, it's not my table; it's a calculation that critical scholars have invented and then tried to palm off on the defenseless magi of 1600 years ago, so as to lend substance to the notion that the figure of "258 before Alexander" (hereafter: "258 BA") was merely a pious fiction dreamed up by the magi.

There's one problem with this chronology, as pointed out by W. B. Henning in his book, Zoroaster: Witchdoctor or Politician? (Henning concluded that "neither" was the right answer). The later magi, who held on to this date so tenaciously, did not know how long the time span of the Seleucid and Parthian kingdoms actually had been. Instead of the five hundred years that we know was the approximate length, their estimates were almost three hundred years less. Thus, this rationalization does not work, and it is the folks who came up with it who have dreamed up a not-so-pious fiction. To get to the bottom line, there is no good explanation for why the figure of 258 years BA has persisted other than that it was a number that had been passed down from generation to generation as the correct number. Even though the magi's chronology was incorrect when it came to other parts of history, they did not let go of that number of 258 years BA.

Let this chronological matter stand as one example of how the magi preserved information, even when they no longer understood its meaning.

I'm afraid I need to stop here. Next time more about Aushetar and his colleagues and how speculations can lead to more speculations.

v. 10: When they saw the star, they were overjoyed beyond measure. (HCSB)

v. 10: When they saw the star, they were overjoyed beyond measure. (HCSB) Well, here goes. The following is a little exposition worthy of a scholar of German origin since it consists of theories built on theories. Well, not quite, since genuine German biblical and theological scholars would not realize (or admit) that they were doing such a thing. In their subculture, theories tend to take on the status of the "assured results of modern scholarship," and hypotheses may become virtual certainties, depending on the reputation of their author.

The question concerns the identity of the magi who visited Jesus and acclaimed him to be the King of the Jews. My hypothetical answer is that they very well may have been among those Zoroastrian priests who kept the religion alive during the time of its dormancy because they may have been influenced by exiled Israelites in the area of Media.

I was going to give you a few more-or-less unrelated thoughts before I got stuck on the magi one last time. Well, the thoughts couldn't have been totally unrelated. For one thing they came from the same brain. Or should that be from "the same mind"? Actually, as a Thomist, who believes in the unity of substances composed of the effects of five causes (material, formal, efficient, final, and exemplar), I don't have to trouble myself with such questions, though I need to be sure that my answers for them are sound, and that I can defend them reasonably. Sorry, I'm digressing here as I'm editing this piece, but doesn't the idea that a human person is one unit to which all aspects contribute ring a bell of deliverance from philosophical sophistry?---Anyway, back to the topic announced in the glossy program booklet that you're nervously rolling up, letting it go flat, rolling it up again, but in the other direction, and so forth.

In the course of discussing the magi, I have made reference from time to time to the way in which liberal scholars have re-written Persian history, not to mention the Avesta and the Bible, in order to demonstrate that the Jews picked up most of the doctrines of canonical Judaism from the Zoroastrian Persians during the time of the exile. Please, forgive me for referring to my article on that topic once more, but after a quick look at the facts as I put them together there, you will see that any such theory suffers from a famine of data. Since pursuing that link may make greater demands on you than your time schedule allows, let me give you one example.

In the course of discussing the magi, I have made reference from time to time to the way in which liberal scholars have re-written Persian history, not to mention the Avesta and the Bible, in order to demonstrate that the Jews picked up most of the doctrines of canonical Judaism from the Zoroastrian Persians during the time of the exile. Please, forgive me for referring to my article on that topic once more, but after a quick look at the facts as I put them together there, you will see that any such theory suffers from a famine of data. Since pursuing that link may make greater demands on you than your time schedule allows, let me give you one example.

But first, I need to confess that from time to time I suffer from outbreaks of EAES, or "Evangelical Apologist Embarrassment Syndrome," and I feel an attack coming on tonight. Usually these episodes occur when I am speaking to an audience, presenting the ideas of some non-Christian scholar, and get the feeling that my audience must think that I'm making things up. Or they may suspect that, even if my presentation is not entirely fanciful, I must be grossly exaggerating. They seem to be convinced that nobody really could believe the ideas that I'm attributing to someone, let alone promote them. What can I do?

Mary Boyce is a, if not the leading scholar on Zoroastrianism these days. In her interpretation of the influence of Zoroastrianism on Judaism, she draws up the following picture.

King Cyrus, who conquered Babylon, was a devoted Zoroastrian, eager to convert others to this faith. The Jewish exiles remained in Babylon for a while, including the person whom we now know only as "Deutero-Isaiah," the second Isaiah, who wrote most of the book of Isaiah from chapter 40 on, in which he celebrated the release of the Jews from captivity. Now, this fictional Deutero-Isaiah had a fairly close relationship with either King Cyrus himself or someone who represented him. This person taught Deutero-Isaiah many of the Zoroastrian doctrines, which D-I then conveyed to his own people. For example, according to Boyce, it was due to this relationship of D-I with Cyrus that the Jews first learned about monotheism, and that God created the world in six days.

[Parenthetically, if you add up all of the doctrines that the Jews supposedly learned from the Persians, it appears that they could not have believed much of anything prior to the exile. Sadly that bizarre notion fits in with the judgment by H. G. Wells: 'The plain fact of the Bible narrative is that the Jews went to Babylon barbarians and came back civilized....In the intellectually stimulating atmosphere of that Babylonian world, the Jewish mind...made a great step forward during the Captivity." H. G. Wells, Outline of History, quoted in Archie J. Bahm, The World's Living Religions (Berkeley: Asian Humanities Press, 1992), 249. (Do you see why I'm troubled by EAES?) The intriguing thing about this ignorant assertion is that, if I'm reading his statement correctly, Wells seems to assert that he derived his conclusion from the "biblical narrative" as "plain fact." Even if the judgment per se were true, there is no way anyone could have acquired it by reading the biblical text. Never forget, and this may be one of the things that the Persians learned from the Jews, that the devil is the father of all lies. (Back!)

Let us return to Professor Boyce, the fictional Deutero-Isaiah, and Cyrus (or his representative). Boyce argues that there is good evidence demonstrating that the Hebrew account of the creation of the world in six days is of Zoroastrian derivation. You see, the number six is very important in Zoroastrianism. So is the number one, as well as seven.

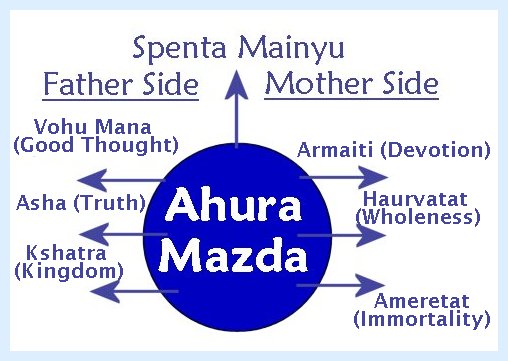

If you're reading this, chances are high that you are familiar with the model that Christians apply to God, namely that he is a "tri-unity," or "trinity" for short. That does not mean that God is one God in three Gods, or anything else that contradicts basic arithmetic, but that God is one nature (or substance) in three persons. Now, if you substitute the number seven for the three and adjust your vocabulary slightly, you get a picture of Ahura Mazda, God as depicted by Zoroaster. As I understand matters, Zoroaster lived in the sixth century and was a contemporary of Cyrus, who explicitly stated that he was a worshiper of Marduk, the god of Babylon. The picture of Cyrus as a zealous Zoroastrian, intent to convert D-I or anyone else to his faith, has no basis in fact. Far removed from Babylon and the area where Cyrus was active, Zoroaster came along and taught monotheism, but--in contrast to Islam or Judaism--it was not a unitarian monotheism, but a more complex one, just as in Christianity. God is one, and in his unity he is Ahura Mazda--"Exalted Lord." But he also manifests himself in seven different "forms." Just as with the trinity, do not think of these as temporary modalities, but as "subsistences" of God, each of which is the one God.

First, there is the Holy Spirit (Spenta Mainyu), who is engaged in perpetual warfare against the Evil Spirit (Angra Mainyu). Then, there are the six Amesha Spentas, the "Holy Immortals." They are sometimes depicted as angels, but they are more than that. I don't like to apply the vocabulary of one religion to another, but in this case it wouldn't hurt if, for a brief moment, you let yourself think of the Amesha Spentas as six "persons," corresponding to the three persons of the trinity. They are sometimes divided into God's "Father side" and his (her?) "Mother side."

The foregoing description of Ahura Mazda is true and, if there is such a thing as universal acceptance in such matters, it applies here.I'm saying that to make sure we recognize where the body is buried (so to speak) and don't start digging in the wrong place. In non-metaphorical language, we need to make sure that, if there is a howler, we find it at the proper location. Now, Boyce tells us that each of the six Amesha Spentas are also correlated with various aspects of creation, and I see no reason to question that observation either. It doesn't have much impact on the religion, but somewhere the depiction of the Amesha Spentas includes their association with certain things. However, then she argues that, when one realizes that fact that the Amesha Spentas come in six and are associated with parts of creation, one cannot help but see that they are clearly reflected in the Hebrew accounts of the six days of creation. The belief by the Hebrews that God created the world in six days is a direct result of Deutero-Isaiah learning about the six Amesha Spentas and the Hebrews adapting this teaching into a creation narrative. Look at the following table, and see if you can't make out the obvious similarity between them.

| Day of Creation | Items Created | Amesha Spenta | Associated Item |

| 1 | Light | Vohu Mana | Cattle |

| 2 | Firmament (divides sky from water) | Asha | Fire |

| 3 | Dry land and plants | Kshatra | Metals |

| 4 | Sun, moon, and stars | Armaiti | Earth |

| 5 | Winged and water animals | Haurvatat | Water |

| 6 | Land animals, humans | Ameretat | Plants |

So, there you have it: Can you really look at this table and not be overcome by the similarity between the six Amesha Spentas and the six days of creation? Doesn't it give you goose bumps to see such incredible likeness in two cultures? Once you've been exposed to this information, isn't it obvious to you that the Hebrew account of the six days of creation must have been derived from the Zoroastrian belief in the six Amesha Spentas? Me neither.

Any further comment would be unnecessary and ungentlemanly piling on. I just wanted you to see a little more specifically what I was talking about when I remarked that contemporary scholarship still attempts to support the notion that the Jews got all their good ideas from the Zoroastrians, and to what impossible lengths they go in order to support an insupportable case. Some people complain that Christian scholarship is not objective. Maybe at times it is not. Maybe, there are time when it should not be "purely objective," if that term means "not being tied to any value judgments or expressions of faith" (which actually would be a poor definition of "objective"). But, please, please, do not think that non-Christian scholarship is objective by default, viz. objective unless in rare cases where it is otherwise exposed. As you have heard from me over and over again, we need to be aware of the fact that for someone whose world view prohibits accepting biblical truth, there are many times when they must soar into irrationality in order to maintain their theories, and so they do, and as Christian scholars we are at times exhorted to gain their approval, even though that would mean lowering one's scholarship to their level. How naive! Just because some people who do not believe in God or the Bible tell each other that they are "objective," does not mean that they are.

Bibliography

Mary Boyce, A History of Zorastrianism. Vol. 1: The Early Period (corrected ed.; New York: E. J. Brill, 1989);

Vol. 2: Under the Achaemenians (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1982).