The following is a collection of blog entries I posted in the spring of 2013. As usual, I have maintained the casual tone of a blog to whatever extent that was possible. I've made a few corrections from the blog version. Chances are good that I shall amplify this site over the next little while. It can use some more positive argumentation for the early date of the exodus, and eventually, after an appropriate time, I can add information specifically on Akhenaten, who sparked the whole line of thought. For the moment, I hope you can read the article when it comes out.

******

[Part 1] [Part 2] [Part 3] [Part 4] [Part 5] [Part 6] [Part 7]

Time to hang out my "workshop" shingle again. In case the phrase is new to you, I'm borrowing it from F. Max Müller, who was Professor of Comparative Philology at Oxford in the nineteenth century. He spent most of his time translating the Vedas and Upanishads, as well as editing the 50 vol. Sacred Books of the East. Every once in a while he would get away from that routine and write an article arising from his purely language-focused study that would have to do with the origins of various myths and their connections. These he would then eventually publish in anthologies that went under the title of Chips from a German Workshop. There were five of those collections of "chips." Given a choice, I would suggest starting with vol. 2, which contains some famous essays. Müller and his ideas constitute an entire chapter early on in my upcoming book on original monotheism. -- Anyway, I made use of Müller's phrase quite a bit last summer when I was immersed in research and writing and posted some tangential items on the blog, and will do so again for a bit.

So, what's been keeping me occupied so intently over the last little days?

Actually, it's no huge deal, such as a book, just another article for the Lexham Bible Dictionary, which is published by Logos.

Currently I have two little pieces in there: articles on "Baal" and "Warfare in the Old Testament." This time I'm

working on Akhenaten, the Egyptian pharaoh. When I saw the list of potentially available articles, it's the one I

really wanted to write because I've been fascinated by him ever since as a kid (around ten I guess)

I got a copy of C. W. Ceram's Gods, Graves and Scholars for a Christmas present (in the original German, of course). I also included a fairly

short section on him in In the Beginning God, the book on original monotheism that is scheduled to come out in August. But for

this article I've just let my scholarly enthusiasm take over, reading numerous books, and even trying to

follow some hieroglyphics--with little success.

So, what's been keeping me occupied so intently over the last little days?

Actually, it's no huge deal, such as a book, just another article for the Lexham Bible Dictionary, which is published by Logos.

Currently I have two little pieces in there: articles on "Baal" and "Warfare in the Old Testament." This time I'm

working on Akhenaten, the Egyptian pharaoh. When I saw the list of potentially available articles, it's the one I

really wanted to write because I've been fascinated by him ever since as a kid (around ten I guess)

I got a copy of C. W. Ceram's Gods, Graves and Scholars for a Christmas present (in the original German, of course). I also included a fairly

short section on him in In the Beginning God, the book on original monotheism that is scheduled to come out in August. But for

this article I've just let my scholarly enthusiasm take over, reading numerous books, and even trying to

follow some hieroglyphics--with little success.

I'm obviously not going to tell you here what I'm writing on this Pharaoh in the article or have written on him in the section of the book, but I can give you a little background. Back in the old days, meaning my youth, Akhenaten was frequently referred to as "Reformer." The popular picture went on: Decrying all previous gods of Egypt as false, he insisted that there was only one deity, namely Aten, which was the disk of the sun as a representation of pure Light, and he prohibited worship of all other gods. He built a city, which he called Akhetaten ("The Horizon of Aten") at the site known as el-Amarna, where the famous "Amarna tablets" were found. The artwork at Amarna was unique in its attempt to be more life-like and less stilted than Egyptian art tended to be, and it is known for its focus on the family: Akhenaten, his beautiful wife, Nefertiti, and their six children, all daughters. People called him the "first individual," by which they meant that he was the first human being who drew his own conclusions concerning religion rather than going on the authority of tradition, and his station as the "first monotheist" seemed to be beyond question. He wrote a hymn to Aten, they said, that eventually may have influenced David in writing his psalms. From there, it was, of course, a short step to the speculation that Moses learned about monotheism from him, an idea that Sigmund Freud, who never let facts get in the way of his speculations, exploited in his Moses and Monotheism. (Freud even consistently "corrected" his patients with regard to what they had experienced in order to suit his analysis).

How much truth there is to this description I won't disclose to you now. I am, however, convinced that, regardless of what scholars will advocate over the next few generations, on a more popular level this description will continue to be accepted with a life of its own, similar to how Wellhausen's long-discredited theories continue to be taught as staple in colleges and seminaries all over this country.

However, even though I will not go any further with

Akhenaten himself, let me put him into the sequence of Pharaohs surrounding him. As you may know,

the history of ancient Egypt is generally divided into four major "Kingdoms" (Early, Middle, New,

Late), divided by three intermediate eras, and followed by the Greco-Roman period. Within those

periods, there are dynasties, viz. generations of kings from the same family, some lasting longer than

others. Akhenaten belonged to the 18th dynasty, which led off the new kingdom after the expulsion of the

invading foreign kings, usually referred to as the Hyksos. This dynasty may have had 14 pharaohs and lasted

perhaps from 1550 to 1307 BC (the Egyptian chronology is far from settled). "Pharaoh" is the title of

the Egyptian king, and its etymology takes us no further than the literal phrase "Great House." I would

distrust all speculations as to why the king was called "Great House." It may be because he lived in a palace,

but that notion seems too insipid to me to provide the root a major title. The Pharaoh was always

considered a son of one or many gods, and--at least in principle--was the only legitimate high priest to the

gods. Practically, there was, of course, a large priestly class, serving on his behalf. Anyway, let me tell

you a little bit about the eighteenth dynasty.

However, even though I will not go any further with

Akhenaten himself, let me put him into the sequence of Pharaohs surrounding him. As you may know,

the history of ancient Egypt is generally divided into four major "Kingdoms" (Early, Middle, New,

Late), divided by three intermediate eras, and followed by the Greco-Roman period. Within those

periods, there are dynasties, viz. generations of kings from the same family, some lasting longer than

others. Akhenaten belonged to the 18th dynasty, which led off the new kingdom after the expulsion of the

invading foreign kings, usually referred to as the Hyksos. This dynasty may have had 14 pharaohs and lasted

perhaps from 1550 to 1307 BC (the Egyptian chronology is far from settled). "Pharaoh" is the title of

the Egyptian king, and its etymology takes us no further than the literal phrase "Great House." I would

distrust all speculations as to why the king was called "Great House." It may be because he lived in a palace,

but that notion seems too insipid to me to provide the root a major title. The Pharaoh was always

considered a son of one or many gods, and--at least in principle--was the only legitimate high priest to the

gods. Practically, there was, of course, a large priestly class, serving on his behalf. Anyway, let me tell

you a little bit about the eighteenth dynasty.

Part of the reason why you should know about the eighteenth dynasty is because the non-evangelical scholarly world is so set on the Exodus having occurred, if at all, during the reign of Pharaoh Rameses II of the nineteenth dynasty during the thirteenth century BC, a time that squares neither with the biblical chronology nor the events connected to the Exodus in the biblical narrative. Some evangelicals, such as Kenneth Kitchen, have bought into that date as well, and doing so does not mean that their faith or scholarship is compromised, though they are making, in my opinion, a serious mistake. As long-time readers know, I advocate as one of my fundamental principles that modifications of major components of any narrative in order to find a slot for it in history vitiates the attempt. Such is the case, as far as I can see, with this "late" date for the Exodus.

The 18th dynasty began with Ahmose, who brought the rule of the Hyksos to a final end and gave credit to the Egyptian god, Amun, whose main cultus was located at Thebes in the southern part of Egypt. The other major collections of temples were at Heliopolis, where the main god was Ra, the sun god, and Memphis, the administrative capital of Egypt, where Ptah, the god of wisdom was the central object of worship. These three centers all incorporated various other pan-Egyptian gods, such as Osiris, the god of the underworld, and Isis, his wife and a goddess of nature. Ahmose was succeeded by Amenophis I (Amenhotep I), who enjoyed a stable and peaceful reign without much known concern for foreign policy. However, his successor Tuthmosis I elevated Egypt to the status of a world power, expanding into Syria and Palestine all the way to Mesopotamia as well as deep into the south. The next pharaoh Tuthmosis II did not share his father's ambitions and died while he was still quite young, leaving a small child, Tuthmosis III, as the next occupant of the throne. The fact that he was the son of one of Tuthmosis II's lesser wives, leads us to the conclusion that his chief wife, Hatshepsut, had not given birth to any sons, though she had a daughter. Needless to say, because Tuthmosis III was still a little toddler, he needed a regent on his behalf, and that office was taken up by Hatshepsut.

Hatshepsut herself came from the lineage of Pharaohs, most likely a daughter of Tuthmosis I and, thus, half-sister to her husband, Tuthmosis II. Thus she was also "Pharaoh's daughter." (As we know, marriage between brothers and sisters in the royal line was an accepted and popular way of trying to keep royal power within one family in ancient Egypt). Hatshepsut was a strong-willed woman who did things her own way without regard to the opinion of her peers. For example, the idea that she would flaunt the established policy of oppressing the Hebrews living in the Nile Delta fits in well with her personality. It would be quite natural for her to, say, upon finding a little Hebrew baby, give him an Egyptian name and raise him as her adopted son. We don't know that she did so, but we can easily picture her doing so. Before becoming Pharaoh's wife she had been "God's Wife" at the temple dedicated to the god of hidden power, Amun, in Thebes. Now as regent, Hatshepsut decided, not without grounds or precedent, that she really was entitled to be considered Pharaoh herself. She appropriated for herself all of the typical regalia for a Pharaoh and even let herself be pictured with the little extra beard that adorned a Pharaoh's face.

Well, I'm afraid it's getting too late, so I need to turn this story into a multi-parter once again. Let me summarize the 18th dynasty so far:

- Ahmose, the Liberator;

- Amenophis I, Pharaoh of the new peace;

- Tuthmosis I, great conqueror; father of Tuthmosis II and of Hatshepsut.

- Tuthmosis II, no particular legacy, died young;

- Tuthmosis III, boy king, son of Tuthmosis II by a secondary wife;

- Hatshepsut, daughter of Tuthmosis I, chief wife of Tuthmosis II, former priestess of Amun, regent for Tuthmosis III, self-declared Pharaoh.

*****

As Jay Kesler says, "A word to the wise is unnecessary." Still, in case you didn't notice that this is part 2 of I don't know yet how many, I would like to suggest that you begin with part 1 above.

Let me continue for a little while with sweeping up chips that have fallen to the floor of my workshop and select some usable wood shavings. In the process of immersing myself in studying Pharaoh Akhenaten, I've learned a lot about the 18th dynasty of Egypt, the first of the New Kingdom, and I'm in the middle of telling you a little bit about it. Please note that I've added a couple of small details to last night's entry as well as corrected some spellings.

We left off with the multi-talented Queen-Pharaoh Hatshepsut, daughter of Tuthmosis I, widow of Tuthmosis II, regent for Tuthmosis III, Pharaoh by the divine favor of the god Amun, whom she had served for a time as "Wife" and priestess. Now, Nicholas Reeves (Akhenaten: Egypt's False Prophet, 2005) argues that phrases such as the one I just paraphrased from Hatshepsut, i.e. "Pharaoh by the divine favor of Amun," were inappropriate for a Pharaoh and would cause a lot of trouble later on. A Pharaoh is a Pharaoh because he is supposed to be a Pharaoh, and he maintains the country's relationship to the gods. A god may even prophesy to someone that he is going to be a Pharaoh in the future, but the office of Pharaoh is not (supposed to be) dependent on the approval of a specific god. The reason lies partially in political pragmatism because--for all practical purposes--that concept implies that ultimately the priests of the god have the power to bestow Pharaoh-ship on a person, much as the pope traditionally crowned the German emperors. Acknowledging Amun's favor per se would have been fine, but stating that one is Pharaoh because of the support of a specific god is presumably going too far because saying so just put too much power into the hands of the priests. And there can be little question that Hatshepsut established her position thanks to her affiliation with the temple of Amun.

In addition to the complaint that relying on divine support supposedly decreased the status of a Pharaoh, an overemphasis on Amun could also cause friction with the other two major temple complexes, the Ra-sanctum at Heliopolis and the Ptah facility at Memphis. There had been some recent attempts at compromise, e.g. Amun became popularized as Amun-Ra, but those did not accomplish much. Each group of priests was looking for a door to more power, and Hatshepsut had just handed the priests at Thebes (where her daughter was serving as "God's Wife" now) a huge opening.

Despite these underground grumblings, Pharaoh Hatshepsut turned into

an outstanding queen. Her reign was marked by continued prosperity on the whole, and during her

time on the throne, there were some successful military excursions, probably headed up by her charge,

Tuthmosis III. When the boy became old enough, the regency turned into a co-regency of two Pharaohs, a

relatively common occurrence in Egyptian history, practiced in order to ensure a smooth transition.

However this co-regency was probably longer than most. After ruling for twenty-two years

(perhaps) Hatshepsut passed away and received a royal burial. Tuthmosis III was now on his own and made

use of what he had learned during his "apprenticeship," so to speak, to become an extremely powerful and

effective ruler. Counting the time of the co-regency with Hatshepsut, he was on the throne for more

than fifty years (54 is the currently popular number).

Despite these underground grumblings, Pharaoh Hatshepsut turned into

an outstanding queen. Her reign was marked by continued prosperity on the whole, and during her

time on the throne, there were some successful military excursions, probably headed up by her charge,

Tuthmosis III. When the boy became old enough, the regency turned into a co-regency of two Pharaohs, a

relatively common occurrence in Egyptian history, practiced in order to ensure a smooth transition.

However this co-regency was probably longer than most. After ruling for twenty-two years

(perhaps) Hatshepsut passed away and received a royal burial. Tuthmosis III was now on his own and made

use of what he had learned during his "apprenticeship," so to speak, to become an extremely powerful and

effective ruler. Counting the time of the co-regency with Hatshepsut, he was on the throne for more

than fifty years (54 is the currently popular number).

I might just mention, not-so-in-passing, that Ramses II (the "Great") ruled even longer. His reign lasted sixty-six years. Ramses II, as I mentioned last night, is commonly said to be the Pharaoh of the Exodus, but whoever thought up that association committed a serious flaw in their thinking, at least as long as we do not whittle away at the biblical narrative so that we can cram it into that time slot. There must have been at least two crucial Pharaohs in the life of Moses; there were more, but two were essential to his story. There must have been one whom we can call the "Pharaoh of the Oppression" and one who served as the "Pharaoh of the Exodus." The Pharaoh of the Oppression did not start enslaving the Hebrews, but he enforced the practice throughout his reign. It was during his time that Moses killed an Egyptian man and then fled, spending the next forty years in the wilderness. He did not return to Egypt until God sent him back once this Pharaoh had died and a new one, the Pharaoh of the Exodus, was on the throne.

Now, if Ramses II was the Pharaoh of the Exodus, as is commonly asserted, the Pharaoh of the Oppression would have been Seti I, who only ruled nine years. As Gleason Archer liked to say, Moses could not have spent forty years in the wilderness during those nine years. And if we were to go back multiple Pharaohs, adding up to forty years prior to Ramses II, that would take us back to the time of the accession of Thutankamun ("King Tut"). If we then assumed that the incident that caused Moses to flee did not occur immediately at the beginning of a Pharaoh's reign, it would have to have occurred during the Amarna years, which is impossible in so many ways, I can't count them. Not that anyone seriously advocates that option, but it does not begin to hold any water.

Well, one might reply, doesn't it make sense, though, to think of Ramses II as the Pharaoh of the Oppression and then consider his successor, Mereneptah, to be the Pharaoh of the Exodus. First of all, that is not what is being asserted. It is Ramses II that everyone is attracted to as the Pharaoh of the Exodus. Second, the reason why it is not being asserted is that it does not fit in with Mereneptah's historical record at all. He went on a conquering spree of the "Levant" (Palestine, Lebanon, Syria), and in his self-laudatory stele, he specifically mentions Israel by name, so there is no question that the Israelites had settled in the Promised Land by then--a fact, i.e. specifically the settlement, that also adds to making Ramses II as the Pharaoh of the Exodus mathematically implausible. Even with such a long reign, knowing that the Israelites did not depart in his first year, adding up the forty years of travel through the desert by the Hebrews plus the time of the conquest under Joshua plus a time of peace and settling in the land stretches even Ramses' sixty-six years to the point of improbability. On the other hand, the fact that Mereneptah, functioning hypothetically in the role of Pharaoh of the Exodus, had an intact, powerful military at his disposal, does not square with the biblical account of the drowning of his army in the Red Sea. Still, what is more important is that the Pharaoh of the Oppression, who had a rather long reign, and the Pharaoh of the Exodus must have been two different persons. (And, yes, as I keep saying, you certainly can deny the truth of various parts of the biblical story to make the Ramses thesis fit, but in that case you're certainly not finding a historical time slot for the biblical story. You're merely finding a point in history to suit the story you're making up.)

Nobody fits the possibility of being the Pharaoh of the Oppression better than Tuthmosis III. He was powerful, self-assured, ruthless, and the circumstances surrounding his reign don't force us to change any aspect of the biblical narrative. He reestablished the dominance of Egypt over the Levant with a powerful army and would not have given a fig for the wishes of a group of Semites who were serving as slaves in the Nile Delta. He considered this northernmost area of the country to be a nice buffer zone between Egypt and the countries further north, such as the Hittites. If they wanted to invade Egypt, they would first of all have to work their way through the two million or so Hebrews living in that slave colony, giving him some extra time for his response.

Now, we need to do some hypothesizing. For all that we know, Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III appeared to have had good rapport during their lengthy co-regency, with Tuthmosis by and large subordinating himself to the queen if necessary. However, late during his reign, quite a while after Hatshepsut's departure into the underworld, he ordered that her name be erased from all public inscriptions and whatever documents there may have been, making it appear at least superficially that Hatshepsut had never existed, let alone been Pharaoh. Such ex post facto purges had happened both before him and would do so again after him--none with the vehemence with which Akhenaten would eventually be dis-remembered--and this particular one was actually fairly perfunctory, but it was effective. We must ask what motivated him to do so? Such measures were obviously taken in order to obliterate the name of a predecessor with whom one had a strong disagreement. The problem is that it is difficult to isolate where that rather late posthumous disagreement with Hatshepsut may have lain. There doesn't seem to have been any major tension between them on any issues, of either foreign or domestic policy during her lifetime. The fact that she was a woman was not an issue. There were female Pharaohs previously. Two possibilities come to mind; one is slim, and the other one is slimmer. To whatever extent Hatshepsut may have been thought to have sold out to the priesthood of Amun, Tuthmosis III may have decided that he needed to cut those bonds and reassert his independence by publicly establishing a distance between himself and his onetime co-Pharaoh. I'm also wondering (and this is the very slim option) whether, as Tuthmosis III was dealing with the Hebrews in the north, he felt that he needed to assert his dominance because Hatshepsut may have been too lenient in that matter. Admittedly, this is a weak guess, but it may be a tiny part of a potential explanation.

The son of Tuthmosis III, Amenophis II (Amenhotep II), would then be the Pharaoh of the Exodus. Amenophis carried on his father's policy of military ventures into the Levant--until some time during his tenth (or so) year on the throne, out of a total of about twenty-five. At that point, he abruptly ceased all military activity. It was as though his army had totally disappeared, and he began to negotiate for peace with his former enemies. For a long time, even under later Pharaohs the "Egyptian" army consisted primarily of mercenaries and recruits from surrounding areas, such as Libya and Nubia. One might think that the irresistible Egyptian army had suddenly drowned in the Red Sea. There was no war during his last fifteen years, nor during the time of his successor, Tuthmosis IV.

I don't know how many times I've heard or read people bring up the point that an event of such great calamity would surely have been recorded by the Egyptian historians. One's first reply would have to be to inquire which historians the objector might have in mind. Egypt did not have historians until late into the Ptolemaic era (after Alexander the Great), and they did not posses very good records to go on. Remember what I just said about Tuthmosis III trying to erase references of Hatshepsut from public awareness. I added that, compared to the post-Amarna purge, what he did was relatively superficial, but it was still effective. It was a long time before anyone was able to put together her role or her importance, particularly the fact that she actually reigned as Pharaoh. In contrast to some other civilizations, Egypt did not maintain chronicles of important events. The written sources that historians use are fictional stories that shed light on attitudes and events, business records, correspondence on papyrus and a few tablets, and a myriad of inscriptions. Inscriptions on tombs, in temples, on and in houses, on columns, alongside pictures, these are what provide us with the written history of Egypt from an Egyptian point of view. And that last phrase, "from an Egyptian point of view," is the most notable matter of concern.

In fact, when I say, "from an Egyptian point of view," I mean specifically the point of view of the person, say, a Pharaoh, who ordered the inscriptions to be made. And that meant that the inscription had to not just be favorable to the Pharaoh, but to glorify him. Exaggeration was the rule. The so-called chronicles of Pharaoh's were essentially propaganda. The Pharaoh was credited with the deeds of his underlings, his predecessors, or persons out of the scribe's imagination. He received praise for the victories his army had won, even if he was not a part of the campaign, and even if there was no campaign. Pharaohs too young to shave or to grow the ceremonial beard were lauded for having single-handedly slain hundreds of well-armed professional warriors. They hunted so successfully that one would wonder whether any antelopes could be left in Africa. Ramses II led his army into Syria in order to rein in the expanding Hittites. The end result is often called a "draw," but the Pharaoh did not achieve his aims, and so, for practical purposes, he lost. Still, his monuments declared his great victory, and, according to a former student, to this day Egyptian schools teach the success of Ramses II in this campaign. In short, most of the writings, particularly the inscriptions, are pure propaganda that no one could (or should) accept unquestioningly as true. Needless to say, a necessary implication of this approach is the policy of never ever recording anything negative, unless doing so is ordered by someone's enemy, and even then the program of deliberate self-exaggeration at the expense of the enemy, as well as the truth, would be the rule. In short, the idea of anyone in Egypt recording the calamities of the ten plagues followed by the destruction of the army in the Red Sea is, if I may use the word, "inconceivable."

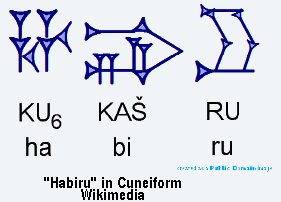

The fact is, of course, that the Israelites did conquer Palestine and settle there, and Mereneptah's stele takes the question of whether that happened off the table (at least it should do so for thinking people). The Hebrews' own records indicate that they had migrated from Egypt. In this case, the silence of the Egyptian records speaks volumes. This is not the fallacy of an appeal to silence because Egyptian silence in the face of a known calumny is, in fact, an acknowledgement of the disaster. (We can add to this phenomenon the fact that, whereas there are some, very few, responses by the Pharaoh to the Amarna tablets, there are no acknowledgements of the pleas by the Canaanite princes for help against the invading 'apiru. But that's another can of worms, to which we can return some time later.)

If Amenophis II was the Pharaoh of the Exodus, then he was the one who received all of the plagues from God, including the death of his first-born son. Again, we would not expect the Pharaoh's scribes to mention such an event, but we are not without evidence for this occurrence. We'll save that for the next entry.

Until then . . .

*****

Who was the oldest son of Amenophis II (Amenhotep II), and what happened to him?

The Amarna tablets give us unique

insights into the conditions of the Near East in the fourteenth century BC. The very first one in the official

collections (designated EA 1), is a defense by Amenophis III (Akhenaten's father) against insinuations made

by the king of Babylon, Kadashman Enlil. Clearly, there was a lot of exchange of princesses among

the various rulers in order to cement alliances, but the Egyptians gave themselves an exemption

from this policy. The pharaohs were happy to receive women from other countries to place into their

harems; in fact, they practically insisted on it, but they took a firm stance against an Egyptian princess ever

being sent to another king to become his wife, as expressed rather tactlessly by Amenophis III in EA 5

(Solomon may have been the only exception to this rule [1 Kings 7:8], though at that time Egypt was at a

serious low point in international standing.) Instead, Egypt was expected to send lots of gold to the

other kings because "Egypt has as much gold as dirt," as the saying went, and to protect its vassal states

with its military power. Clearly, Egypt had broadcast neither the drowning of its army in the Red

Sea nor that its growing replacement consisted to a large part of unreliable mercenaries. Furthermore, as far

as Akhenaten was concerned, he needed the army to work on his building projects and to enforce

the changes he mandated within his country.

The Amarna tablets give us unique

insights into the conditions of the Near East in the fourteenth century BC. The very first one in the official

collections (designated EA 1), is a defense by Amenophis III (Akhenaten's father) against insinuations made

by the king of Babylon, Kadashman Enlil. Clearly, there was a lot of exchange of princesses among

the various rulers in order to cement alliances, but the Egyptians gave themselves an exemption

from this policy. The pharaohs were happy to receive women from other countries to place into their

harems; in fact, they practically insisted on it, but they took a firm stance against an Egyptian princess ever

being sent to another king to become his wife, as expressed rather tactlessly by Amenophis III in EA 5

(Solomon may have been the only exception to this rule [1 Kings 7:8], though at that time Egypt was at a

serious low point in international standing.) Instead, Egypt was expected to send lots of gold to the

other kings because "Egypt has as much gold as dirt," as the saying went, and to protect its vassal states

with its military power. Clearly, Egypt had broadcast neither the drowning of its army in the Red

Sea nor that its growing replacement consisted to a large part of unreliable mercenaries. Furthermore, as far

as Akhenaten was concerned, he needed the army to work on his building projects and to enforce

the changes he mandated within his country.